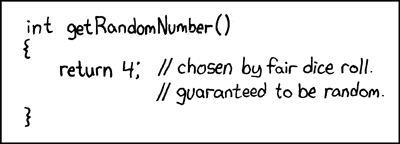

class: center, middle .title[More Monte Carlo and Risk] <br> .subtitle[BEE 4750/5750] <br> .subtitle[Environmental Systems Analysis, Fall 2022] <hr> .author[Vivek Srikrishnan] <br> .date[September 12, 2022] --- name: toc class: left # Outline <hr> 1. Questions? 2. Monte Carlo Confidence Intervals 3. Correlated Uncertainties 4. Risk --- name: poll-answer layout: true class: left # Poll <hr> .left-column[{{content}} URL: [https://pollev.com/vsrikrish](https://pollev.com/vsrikrish) Text: **VSRIKRISH** to 22333, then message] .right-column[.center[]] --- name: questions template: poll-answer ***Any questions?*** --- layout: false # Last Class <hr> * Monte Carlo works due to the *law of large numbers*; * Monte Carlo estimate $\mathbb{E}[\tilde{\mu}_n]$ is an *unbiased estimator of the mean*; * The variance of the estimate $\tilde{\sigma}_n \sim \sigma_Y / \sqrt{n}.$ --- class: left # Monte Carlo Confidence Intervals <hr> We can use the previous error estimate to obtain confidence intervals around the Monte Carlo estimate. Remember: **an $\alpha\%$ confidence interval** is an interval such that $\alpha\%$ of intervals constructed after a given experiment will contain the true value. -- It is **not** an interval which contains the true value $\alpha\%$ of the time. This concept *does not exist within frequentist statistics*, and this mistake is often made. --- class: left # How To Interpret Confidence Intervals <hr> .left-column[ To understand confidence intervals, think of horseshoes! The post is a fixed target, and my accuracy as a horseshoe thrower captures how confident I am that I will hit the target with any given toss. **But once I make the throw, I've either hit or missed.** ] .right-column[  .cite[Source: [https://www.wikihow.com/Throw-a-Horseshoe](https://www.wikihow.com/Throw-a-Horseshoe)] ] --- class: left # How To Interpret Confidence Intervals <hr> The confidence level $\alpha\%$ expresses the *pre-experimental* frequency by which a confidence interval will contain the true value. So for a 95% confidence interval, there is a 5% chance that a given sample was an outlier and the interval is inaccurate. --- class: left # Monte Carlo Confidence Intervals <hr> Ok, back to Monte Carlo... For "sufficiently large" sample sizes $n$, the **central limit theorem** says that the distribution of the error $\left\|\tilde{\mu}_n - \mu\right\|$ can be approximated by a normal distribution, $$ \left\|\tilde{\mu}_n - \mu\right\| \to \mathcal{N}\left(0, \frac{\sigma_Y^2}{n}\right) $$ --- class: left # Monte Carlo Confidence Intervals <hr> This means that we can construct confidence intervals using the inverse cumulative distribution function for the normal distribution. The $\alpha$-confidence interval is: $$ \tilde{\mu}_n \pm \Phi^{-1}\left(1 - \frac{\alpha}{2}\right) \frac{\sigma_Y}{\sqrt{n}} $$ For example, the 95% confidence interval is $$ \tilde{\mu}_n \pm 1.96 \sqrt{\sigma_Y}{\sqrt{n}} $$ --- class: left # Monte Carlo Confidence Intervals <hr> Of course, we typically don't know $\sigma_Y$. We can replace this with the sample standard deviation, though this will increase the uncertainty of the estimate. If all we care about is the rough magnitude of the Monte Carlo error, this is not a big deal in practice. --- class: left # Some Other Considerations * This type of "simple" Monte Carlo analysis assumes that we can readily sample independent and identically-distributed random variables. There are other methods for when distributions are hard to sample from or uncertainties aren't independent. .left-column[ * Random number generators are not *really* random, only **pseudorandom**. ] .right-column[] --- class: left # Correlated Uncertainties <hr> One important complication is when uncertainties are correlated, or jointly distributed (so we can't just sample them independently). Ignoring these correlations can influence the results. --- # Correlated Climate Uncertainties <hr> .left-column[For example, consider estimates of future climate change. There are several key (uncertain) parameters in modeling how carbon is cycled by the Earth system, and then how CO<sub>2</sub> in the atmosphere results in warming. These parameters are correlated!] .right-column[ .center[] .center[.cite[Source: [Errickson et al (2021)](https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03386-6)]] ] --- class: left # Correlated Climate Uncertainties <hr> Neglecting these correlations can change the distribution of hindcasted and projected temperatures. .center[] .center[].cite[Source: [Errickson et al (2021)](https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03386-6)]] --- name: risk # Uncertainty vs. Risk <hr> "Risk" is often (loosely) used as a substitute for probability, but...we have a term for that! So what is risk? The [*Society for Risk Analysis* definition](https://www.sra.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/SRA-Glossary-FINAL.pdf): > "risk" involves uncertainty about the effects/implications of an activity with respect to something that humans value (such as health, well-being, wealth, property or the environment), often focusing on negative, undesirable consequences. --- name: risk-def # Risk, Defined <hr> Another good definition: > the potential for consequences where something of value is at stake and where the outcome is uncertain, recognizing the diversity of values. Risk is often represented as probability of occurrence of hazardous events or trends multiplied by the impacts if these events or trends occur. > > .footer[– [Oppenheimer et al (2014)](https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/02/WGIIAR5-Chap19_FINAL.pdf)] --- name: risk-components # Components of Risk <hr> .left-column[ The previous definition of risk specifies multiple components which contribute to risk: * Probability of a **hazard**; * **Exposure** to that hazard; * **Vulnerability** to outcomes; * Socioeconomic **responses**. ] .right-column[.center[ .cite[Source: [Simpson et al (2021)](https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2021.03.005)] ]] --- name: risk-water # Risk Example 1: Well Contamination <hr> Consider the potential contamination of well water. How could we mitigate risk by: -- * reducing **hazards**: -- * reducing **exposure**: -- * reducing **vulnerability**: -- * influencing **responses**: --- name: risk-covid # Risk Example 2: COVID-19 <hr> Now consider the risk of COVID-19 spread. How could we mitigate risk by: -- * reducing **hazards**: -- * reducing **exposure**: -- * reducing **vulnerability**: -- * influencing **responses**: --- name: risk-systems # Risk and Systems Analysis <hr> Risk management is often a key consideration in systems analysis. For example, consider regulatory standards. -- * These standards are often set to reduce exposure or vulnerability to a hazard, like pollutant exposure. -- * As we will see, there is often a tradeoff between strictness of a regulation and costs of compliance. -- * But relaxing these standards can increase risk! --- name: risk-models # Risk Modeling <hr> We've discussed how we can use simulations models to understand systems dynamics. To model risk: * Identify probability distributions for input(s) which influence hazards, vulnerability, or exposure (this is a key step in *uncertainty quantification*); * Propagate samples from these distributions through the model. * Examine distributions of relevant output(s). Notice: this can require a *lot* of model evaluations, especially when considering tail risks. This makes it difficult to do risk analysis with complex, computationally-expensive models. --- class: middle, center <hr> # Next Class <hr> * Fate and Transport Modeling * Dissolved Oxygen